“Even while human testosterone has been diminishing for thousands of years, testosterone has seen an especially dramatic dropout in recent history. A truly massive drop. All about the time estrogenics have been rising, ‘coincidentally’.” – Anthony Jay

I was recently reading a book called Estrogeneration by Anthony Jay and it floored me. It’s one of those pieces of literature that opens your eyes, not just lightly, but wide enough to make you consider drastic changes to the way you live. The underlying premise of the book, as the title implies, is that humans are constantly exposed to a wide array of compounds that mimic estrogen and this can have deleterious consequences in the long run. The effects of estrogen-like compounds on androgen production in humans is only one of many other variables that affects the endocrine system. Let’s explore why testosterone levels have been progressively declining in males.

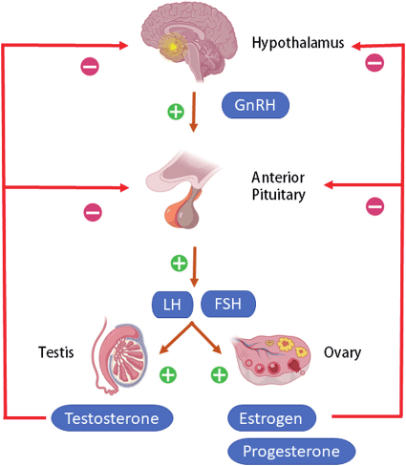

Before we get into the nitty gritty of testosterone and it’s progressive decline, it’s important to understand how the body produces it, starting all the way in the brain. The feedback loop that controls levels of testosterone is referred to as the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.

Basically, the brain, through the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, decides whether to produce the hormones that signal the testes to produce testosterone, based on what the circulating amount of the hormone in the body is. If testosterone declines, gonadotropin-releasing hormone gets released, signalling the anterior pituitary gland to produce luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, stimulating the testes to produce testosterone. If testosterone increases, Gn-RH production declines and the proceeding hormonal cascade results in a drop of testosterone levels (Gupta et al., 2021).

Stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

Stress is a well-established driver of all sorts of illnesses and syndromes and there are links between chronic stress and hypogonadism. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is the communication highway of stress in the body and can interfere with the HPG axis. In chronic stress, activation of the HPA axis leads to increases in glucocorticoid hormones, mainly cortisol, which inhibits GnRH production. Additionally, cortisol also increases sex hormone binding globulin, one of the proteins that binds to testosterone, which results in a decrease in free testosterone (Nargund, 2015). Interestingly though, the relationship between the HPG axis and the HPA axis is reciprocal, considering that testosterone decreases glucocorticoid responses to stress. This implies that management of stress helps to optimize testosterone production and that, in itself also manages stress (Toufexis et al, 2014).

Exogenous compounds that contribute to hypogonadism

As mentioned above, there are well-established links between the progressive decline in testosterone levels and the massive influx industrial and modern chemicals that have endocrine-disrupting effects in humans. It is important to understand where all these chemicals can be found in the home, not just the ones that may disrupt testosterone production. Types and sources of endocrine disrupting chemicals include;

- Organochlorine compounds – e.g. hexachlorobenzene and pentachlorobenzene

- Found in some pesticides

- Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAs) – known as “forever chemicals”

- Non-stick cookware

- Food packaging, paper and board

- Clothing textiles (mainly sports clothing)

- Certain cosmetics

- Paints, coating, cleaning detergents, polishes, and protector sprays

- Phthalates – “BPA” being one of the most commonly known phthalates

- Plastics, packaging materials, children’s toys

- Fragrances/perfumes, nail polish

- Vinyl flooring, adhesives and sealants

- Personal care products

- Insect repellent, UV-filter sunscreens, triclosan/triclocarban (used in toothpastes and anti-bacterial body wash) (Metcalfe et al, 2022)

- Heavy metals

- Lead, mercury, cadmium, arsenic

- Certain medications (particularly in long-term use)

EDCs exert their negative effects by either binding to androgen receptors (mimicking hormones) or interfering with genomic pathways that influence hormonal production. For example, phthalates have been shown to inhibit an enzyme (CYP17) involved in testosterone production in Leydig cells of the testes. Other EDCs inhibit 5-a-reductase, an enzyme involved in dihydrotestosterone production from testosterone, therefore interfering with the maturation male features at birth (Gupta et al, 2021). Certain pesticides have been shown to reduce proteins required for steroidogenesis (production of steroid hormones from cholesterol), this may explain why animal models treated with EDCs showed marked reductions in testosterone. Additionally, phthalates and combustion products also decrease testosterone, possibly by interfering with enzymes, such as 3--HSD, that are critical for steroidogenesis (Sharma et al, 2020). Some medications, particularly when used long-term can also interfere with hormone production. Glucocorticoids, for example, can inhibit the HPG axis by interfering with GnRH neurons because the hypothalamus has a high prevalence of glucocorticoid receptors (Mahabadi et al, 2019).

It is also worth expanding on phytoestrogens, naturally occurring endocrine disruptors, which are found in certain foods such as;

- Soy

- Legumes and bean sprouts

- Alcoholic sources (beer, wine)

It is worth noting that phytoestrogens should be criticized on a different merit to synthetic endocrine disruptors as the amount of naturally occurring endocrine disruptors that would need to be consumed in order to exert negative effects is considerably higher than that of synthetic EDs. Human studies highlighting negative effects of phytoestrogens on hormones are limited but male mice exposed to genistein (a phytoestrogen found in soy) showed reduced androgen receptor expression and steroidogenesis. The same phytoestrogen was also shown to downregulate the expression of several testicular genes in utero exposure, implying that phytoestrogens may interfere with foetal development (Adnan et al, 2022).

Symptoms and signs of hypogonadism

It is important to note what hypogonadism presents like in a clinical setting even though the signs and symptoms may be linked to other conditions, as hypogonadism is a common co-morbidity in obese men and those with diabetes type 2. These will vary depending on age of onset, severity of testosterone deficiency and androgen sensitivity of the individual.

- Low libido

- Fatigue

- Erectile dysfunction

- Reduced facial hair growth

- Low testosterone

- Loss of muscle mass or difficulty building muscle

- Gynecomastia (growth of breast tissue)

Aside from signs and symptoms, laboratory assessment of total testosterone, which includes free testosterone and sex hormone binding globulin as approximately 40% of testosterone is bonded to it whilst 58% is bonded to albumin and the remaining 2% is free testosterone. Total testosterone includes albumin-bound testosterone because it is thought that it detaches from albumin during transit to become free, bioavailable testosterone (Basaria, 2014).

Hopefully this gives you a decent overview of just how pervasive endocrine disrupting chemicals are in society and motivates you to take simple steps to mitigate how much exposure you get to them in your home. On a separate article, I’ll discuss what it means to balance hormones and what you can do to increase testosterone naturally.

References

Adnan, M.R., Lee, C.N. & Mishra, B. (2022). Adverse effects of phytoestrogens on mammalian reproductive health. Veterinary medicine and animal sciences, 10(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.7243/2054-3425-10-1

Basaria, S. (2014). Male hypogonadism. Lancet, 383(9924), 1250-1263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61126-5

Gupta, P., Mahapatra, A., Suman, A. & Singh, K.R. (2021). Effect of endocrine disrupting chemicals on HPG axis: a reproductive endocrine homeostasis. Hot topics in endocrinology and metabolism (1st ed). InTechOpen. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.96330

Mahabadi, N., Doucet, A., Wong, A.L. & Mahabadi, V. (2019). Glucocorticoid induced hypothalamic-pituitary axis alterations associated with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Osteology and rheumatology open journal, 1(1), 30-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.17140/ORHOJ-1-109

Metcalfe, C.D., Bayen, S., Desrosiers, M., Muñoz, et al. (2022). An introduction to the sources, fate, occurrence and effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals released into the environment. Environmental research, 207, 112658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.112658

Nargund, V.H. (2015). Effects of physiological stress on male fertility. Nature reviews urology, 12(7), 373-382. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2015.112

Sharma, A., Mollier, J., Brocklesby, R.W.K., Caves, C., et al. (2020). Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and male reproductive health. Reproductive Medicine and Biology, 19(3), 243-253. https://doi.org/10.1002%2Frmb2.12326

Toufexis, D., Rivarola, M.A. & Viau, L.V. (2014). Stress and the reproductive axis. Journal of neuroendocrinology, 26(9), 573-586. https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.12179

Leave a comment