Out of all the systems in the human body, I find the gastrointestinal system to be the most fascinating and to have the most profound impact on our health. But what is it about this long, slimy tube and its accessory organs that endlessly tickles my curiosity? It isn’t surprising why I would devote so much time to thinking about the gastrointestinal system and its myriad of effects throughout the human body, when you consider the enormous portion of our lives that we spend eating and drinking and how every single bite of food and gulp of fluids that we consume embarks on a long journey into the depths of our gut that ends in a bowel movement and that this entire process is completely involuntary (except for chewing).

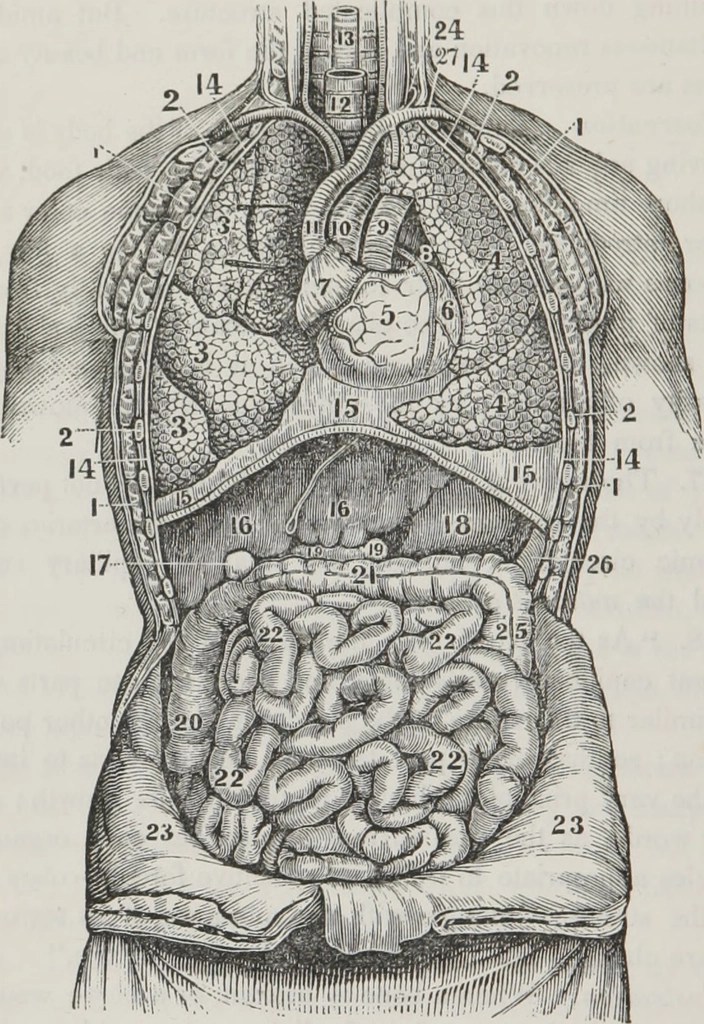

To begin in simple terms, the GIT’s primary function is to digest and absorb the nutrients we need from food and liquids. The gut is the place where the body meets things from the outside world, implying that the gastrointestinal system is the interface between the body and the external environment (Schneeman, 2002). The primary and accessory organs of the gastrointestinal tract and their functions are;

- Mouth

- Food particles are partially broken down through mastication and salivary enzymes (produced by the parotid, submandibular, and sub-lingual salivary glands), which forms a bolus that will be transported to the stomach after swallowing (deglutition), a reflex controlled by the vagus nerve

- Saliva contains ptyalin (salivary amylase enzyme), lysozymes (antibacterial enzymes), lipases, mucin, and immunoglobulin A (saliva is part of the gut’s immune system)

- Food particles are partially broken down through mastication and salivary enzymes (produced by the parotid, submandibular, and sub-lingual salivary glands), which forms a bolus that will be transported to the stomach after swallowing (deglutition), a reflex controlled by the vagus nerve

- Oesophagus

- The approximately 26-centimetre-long tube that contracts, through peristalsis, to propel the bolus of food into the stomach

- Stomach

- The primary site of protein breakdown, extermination of unwanted pathogens, and mixing and grinding of food by peristalsis

- Chief cells secrete pepsinogen, which is converted to pepsin by hydrochloric acid (from parietal cells)

- Pepsin hydrolyses peptide bonds in protein

- Chief cells secrete pepsinogen, which is converted to pepsin by hydrochloric acid (from parietal cells)

- The primary site of protein breakdown, extermination of unwanted pathogens, and mixing and grinding of food by peristalsis

- Liver/gallbladder (accessory)

- The liver synthesizes bile salts and bile acids and the gallbladder secretes them into the duodenum

- Cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid are the main bile acids and they get converted to deoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid by microbiome bacteria

- Bile salts are sodium/potassium derivatives of bile acids and are responsible for the formation of micelles, which facilitate the transport of fats

- The liver synthesizes bile salts and bile acids and the gallbladder secretes them into the duodenum

- Pancreas (accessory)

- Secretes alkaline pancreatic juice into the duodenum (first part of small intestine), which contains enzymes (amylase, lipase, esterase, trypsinogen, chymotrypsinogen, and pro-carboxypeptidase A and B) and neutralizes the acidic contents from the stomach

- Influences digestion of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins

- Secretes insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin, which have important implications in endocrine activity (blood sugar regulation)

- Secretes alkaline pancreatic juice into the duodenum (first part of small intestine), which contains enzymes (amylase, lipase, esterase, trypsinogen, chymotrypsinogen, and pro-carboxypeptidase A and B) and neutralizes the acidic contents from the stomach

- Large intestine

- 1.8-2-metre-long tube that re-absorbs water, sodium and minerals, forms bowel movements, and houses trillions of microbes, known as the microbiome, which produce a variety of compounds that have systemic effects

- Small intestine

- The 6-7-metre-long tube is the primary site of nutrient absorption and handles 9 litres of fluids per day (2 litres from dietary intake and 7 litres from intestinal secretions)

- The intestinal wall is a mucous membrane that is folded into villi, finger-like projections that handle the exchange of nutrients into the systemic circulation

- Completes the digestion of protein, fats, and carbohydrates (Singh, 2007)

- Intestinal epithelial cells play an important role in regulating immune responses in the gut

- Enterocytes, endocrine cells, microfold cells (M cells), goblet cells and Paneth (secrete mucins and antimicrobial proteins) cells influence intestinal permeability and form a defence against antigens, toxins, pathogens and enteric microbiota (Ahluwalia et al, 2017)

Hypothetically speaking, you could classify the brain as part of the digestive system but that would be a generalisation, considering that the nervous system commands every bodily function. However, I will emphasize that the process of digestion technically starts in the brain because the gastrointestinal tract prepares itself to digest a meal before a bite of food is taken, through a series of neural inputs that are stimulated by our sensory interaction with food (sight, smell, touch, and thought). This is the first of the three phases of digestion, referred to as the cephalic (“located on, in, or near the head) phase (followed by the gastric and intestinal phase). The cephalic phase activates the vagus nerve, the chief nerve that innervates through the entire gastrointestinal tract, which triggers a myriad of autonomic responses, including relase of saliva, gastric acid, pancreatic enzymes, and hormones, such as insulin and glucagon (Smeets et al, 2010). The fascinating thing about the vagus nerve isn’t that it connects the nervous system to the digestive, cardiorespiratory, and immune systems and coordinates physiological processes to support homeostasis. It’s that 90% of the nerves in the vagus nerve are efferent, meaning that most of its neurons send signals from the viscera to the brain, not the other way around (Coverdell et al, 2023).

Additionally, digestion is orchestrated by a cascade of hormonal events that influence hunger and satiety and these are referred to as satiety and adiposity signals. Satiety signals involve different hormones than adiposity signals, given that adiposity signals are hormones that are secreted into the blood in direct proportion to the amount of stored body fat. Satiety signals are mainly controlled by glucagon and cholecystokinin (CCK), whereas adiposity signals are controlled by leptin and insulin. Leptin is released by adipocytes (fat cells) and insulin is released by the pancreas and both hormones are released in higher amounts in obese individuals, therefore they serve a net catabolic response by signalling to eat less food and lose weight. CCK stimulates the accessory organs to secrete enzymes and induces satiety by stimulating CCK1 receptors on the sensory fibres of the vagus nerve (Woods, 2004).

The GIT also produces hormones via enteroendocrine cells (EECs) that influence secretion, motility, satiety, metabolism, and postprandial blood glucose levels, such as gastrin (increases gastric acid and pepsin production in the stomach and stimulates motility), histamine (inflammatory mediator), serotonin (influences intestinal motility), and somatostatin (inhibits gastrin, motility, and absorption of glucose, amino acids, and triglycerides) (Greenwood-Van Meerveld et al, 2017).

References

Ahluwalia, B., Magnusson, M.K. & Öhman, L. (2017). Mucosal immune system of the gastrointestinal tract: maintenance between the good and the bad. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology, 52(11), 1185-1193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2017.1349173

Coverdell, T.C., Abbott, S.B.G. & Campbell, J.N. (2023). Molecular cell types as functional units of the efferent vagus nerve. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2023.07.007

Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B., Johnson, A.C. & Grundy, D. (2017). Gastrointestinal physiology and function. Handbook of experimental pharmacology, 239, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2016_118

Schneeman, B.O. (2002). Gastrointestinal physiology and functions. British journal of nutrition, 88(2), 159-163. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/S000711450200226X

Singh, R. (2007, April 2). Molecular physiology: digestive system. Lady Hardinge medical college & Smt. Sucheta Kriplani hospital. https://nsdl.niscpr.res.in/bitstream/123456789/752/1/DigestiveSystem.pdf

Smeets, P.A.M., Erkner, A. & de Graaf, C. (2010). Cephalic phase responses and appetite. Nutrition Reviews, 68(11), 643–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00334.x

Woods, S.C. (2004). Gastrointestinal satiety signals 1. An overview of gastrointestinal signals that influence food intake. American journal of physiology, 286(1), 7-13. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00448.2003

Leave a comment