I have paid homage to antioxidants in previous posts and how indispensable they are for sustaining good health. If I devoted an article to every antioxidant that has been identified in humans and our food supply, I would probably be writing until I retire. So rather than overwhelm myself and everyone else by outlining the functions of as many antioxidants as I can possibly identify, I thought I would emphasise the key functions of them by honing in on glutathione, one of the primary antioxidants in humans that is pivotal in maintaining cellular health, protecting against various disease and aiding a variety of biochemical processes.

In organisms that are dependent on oxygen, energy production is primarily performed in the mitochondria. In this setting, oxygen molecules become susceptible to oxidation during part of the process of energy production, referred to as oxidative phosphorylation. This process reduces oxygen molecules to water and ATP (the chief energy compound) but approximately 1-3% of this oxygen is not converted to water, therefore, mitochondria also generate reactive oxygen species (oxidants) such as superoxide, hydroxyl radicals, and hydrogen peroxide. Glutathione is the most widely distributed redox (oxidation-reduction reaction)-derived sulfur (thiol) compound and it’s antioxidant capacity relays on this thiol group. Besides neutralising reactive oxygen species, glutathione can also mitigate oxidative stress by modulating the concentration of calcium in mitochondria, which is important in neurons, as glutathione will prevent calcium overload and neuro-degeneration after glutamate activation of NMDA receptors (Quintana-Cabrera & Bolaños, 2013).

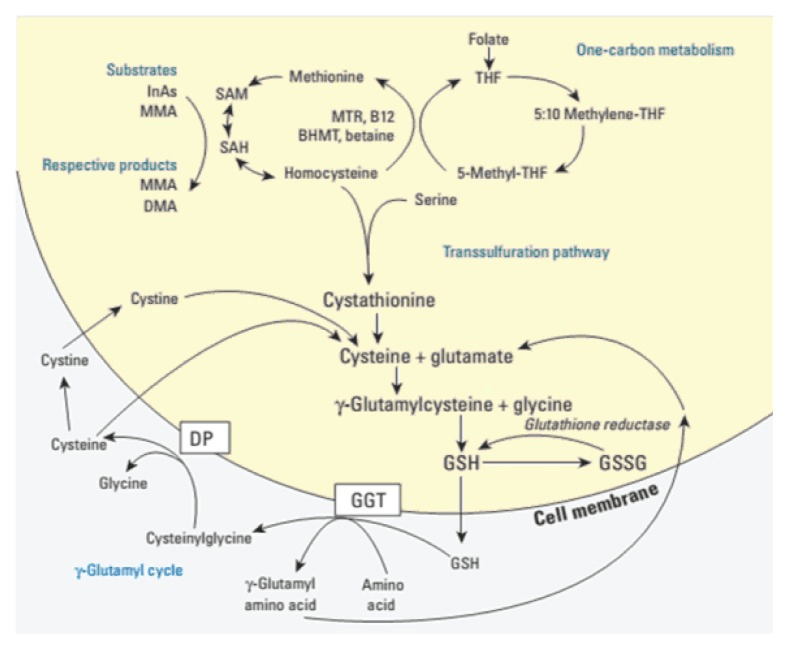

As you can see in the image below, the amino acids cysteine, glycine, and glutamic acid, make up glutathione and it’s synthesis is primarily controlled by the level of cysteine (a sulfur-containing amino acid). Glutathione actually exists in two states, a reduced state (GSH) and an oxidised state (GSSH), and the ratio between them determines a cell’s redox state, which is essentially the balance between oxidants and antioxidants (Franco et al, 2008). Additionally, glutathione is important for phase 2 detoxification in the liver because it binds different toxins, heavy metals, and xenobiotics and conjugates them, making them more water-soluble and ready to excrete via urine or bile. Given that cysteine is the primary ingredient for glutathione synthesis, I should note that during times of oxidative stress (when GSH becomes depleted), glutathione synthesis gets up-regulated by recycling oxidised glutathione (GSSH). Even though it can be seen that there are other methods that our cells use to synthesise glutathione, delving into those is out of the scope of this article (Pizzorno, 2014).

Expanding on glutathione’s antioxidant benefits, tumour cells use an enzyme called nitric oxide synthase to produce nitric oxide, a gas which can react with the cysteine portion of glutathione to form S-nitrosoglutathione and S-nitrosothiols. S-nitrosoglutathione is actually 100 times more potent in neutralising reactive oxygen species than reduced glutathione and given that tumour cells have aberrant reactive oxygen species production, which facilitates their growth, proliferation, and metastasis, glutathione serves to be an important factor in controlling the development of cancerous cells (Kennedy et al, 2020). Additionally, even though glutathione by itself neutralises oxidants, it also supports the regeneration of vitamin C (an antioxidant that protects lipid membranes) and is used to generate other antioxidants, such as glutathione peroxidases, which detoxify lipid hydroperoxides and hydrogen peroxide (Franco et al, 2008) .

Glutathione’s antioxidant activity affects other systems in the body, in particular, the immune system. For example, elevated levels of glutathione and cysteine can suppress the transcription (first step in gene expression) of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1b, interleukin-6, and tumour necrosis factor a. Given that glutathione is the most plentiful peptide in the brain, it would be reasonable to suspect that glutathione’s actions would have major implications in the nervous system. For example, glutathione depletion contributes to increased blood-brain barrier permeability and oxidative stress, which is implicated in neuro-immune disorders, such as depression, chronic fatigue syndrome, and myalgic encephalomyelitis. Furthermore, inhibition of sphingomyelin synthase (an enzyme involved in the myelination of neutrons), caspase activation, and ceramide generation, all drive cell death and inflammation in the brain and occur in oxidative stress-induced glutathione depletion, implying that glutathione is essential for protecting and synthesising new neurons (Morris et al, 2014).

Alluding to glutathione’s immune-enhancing benefits, glutathione can enhance the activity of innate immune cells, such as natural killer cells (large lymphocytes) and neutrophils. Additionally, other immune cells, including adaptive cells, such as T, and Th1/Th2 cells, have shown to be enhanced by glutathione. It appears that glutathione modulates certain cytokines, such as IFN-y and IL-12, which are used by T helper cells to mount an immune response. Glutathione’s immune-enhancing benefits have shown to have favourable outcomes in subjects with infections, such as tuberculosis and AIDS. This could partly be explained by N-acetylcysteine (a precursor to glutathione), which has been shown to block the stimulatory effect of tumour necrosis factor (an inflammatory cytokine) on HIV replication, implying that glutathione could be potent therapeutic agent against viral infections (Morris et al, 2013) & (Ghezzi, 2011).

References

Franco, R., Schoneveld, O.J., Pappa, A., & Panayiotidis, M.I. (2008). The central role of glutathione in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Archives of physiology and biochemistry, 113(4-5), 234-258. https://doi.org/10.1080/13813450701661198

Ghezzi, P. (2011). Role of glutathione in immunity and inflammation in the lung. International journal of general medicine, 4, 105-113. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S15618

Kennedy, L., Sandhu, J.K., Harper, M., & Cuperlovic-Culf, M. (2020). Role of glutathione in cancer: from mechanics to therapies. Biomolecules, 10(10), 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10101429

Morris, D., Khurasany, M., Nguyen, T., Kim, J., et al. (2013). Glutathione and infection. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1830(5), 3329-3349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.10.012

Morris, G., Anderson, G., Dean, O., Berk, M., et al. (2014). The glutathione system: a new drug target in neuroimmune disorders. Molecular neurobiology, 50, 1059-1084. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-014-8705-x

Pizzorno, J. (2014). Glutathione!. Integrative medicine: a clinician’s journal, 13(1), 8-12.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4684116/

Quintana-Cabrera, R., & Bolaños, J.P. (2013). Glutathione and y-glutamylcysteine in the antioxidant and survival functions of mitochondria. Biochemical society transactions, 41(1), 106-110. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20120252

Leave a comment