Out of all the plants and plant-derived substances that we consume on the regular, there is one particular spice that not only tends to reserve a spot in our pantries, but also in the supplement aisle in pharmacies. It seems that turmeric, the yellow spice from the Curcuma Longa plant, not only adds zest and tang to your chicken dish, but can also be a therapeutic aid when taken in supplement form. The question that comes to mind here is that out of all the spices that take up space in our pantries, why does turmeric have the “healthy” reputation that it does, compared to other spices?

Turmeric is predominantly used in Indian cuisine and traditional medicine (Ayurveda), which 70 percent of Indians still rely on for primary care and India is also the largest producer, consumer, and exporter of turmeric. As part of the ginger family of plants, what isolates turmeric as a therapeutic plant from it’s relatives is it’s broad range of over 200 phenolic and terpenoid compounds that have been shown to have anti-mutagenic, anti-cancer, anti-oxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, but the primary compound in turmeric that has undergone the most clinical research is curcumin (Kaur, 2019). Besides curcumin, there are at least 20 compounds in turmeric that have antibiotic properties, 14 that have anti-cancer effects, 12 that have anti-inflammatory effects, and at least ten other compounds that possess antioxidant properties (Ahmad et al, 2020).

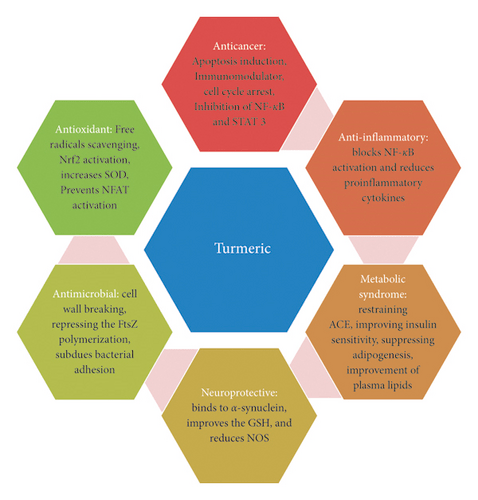

Schematic showing the major therapeutic effects of turmeric (Ahmad et al, 2020)

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects

Out of all the benefits behind turmeric, it’s anti-inflammatory effects are the most frequently cited in it’s therapeutic formulations. Curcumin has been shown to down-regulate/block a wide variety of inflammatory mediators and signalling molecules, such as NF-kB, which targets genes involved in inflammation development and therefore reduces the expression of NF-kB-regulated gene products, including interleukin-1, 6, and 8, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), 5-LOX, MIP-1a, TNF (tumor necrosis factor), CXCR-4, C-reactive protein (CRP), amongst others. These are all examples of curcumin-blocked mediators of inflammation, such as chemokines, cytokines, adhesion molecules, kinases and enzymes. Another example of a pro-inflammatory enzyme that curcumin is thought to inhibit at both a protein and mRNA level is nitric oxide synthase, which generates nitric oxide, a well-known pro-inflammatory mediator (Boroumand et al, 2018). By modifying pro-inflammatory cytokines, curcumin may be a useful adjunct in the treatment of inflammatory conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, as it was shown to have a clinically positive outcome in an in vitro model of intestinal inflammation (Ahmad et al, 2020).

It is well established that oxidative stress underlies the progression of many diseases and continuous efforts are undertaken to develop novel therapeutic ways to mitigate its effects. Curcumin, for example, has been shown to be a potent scavenger of reactive oxygen species, such as hydroxyl radicals and nitrogen dioxide radicals. Additionally, curcumin has also been shown to chelate iron, an important element for humans that can become pro-inflammatory in cases of iron overload, and is also a very potent lipid-soluble antioxidant, protecting lipids from peroxidation. Mitigating oxidative is so important in the grand scheme of things because reducing chronic diseases, DNA damage, mutagenesis/carcinogenesis, and inhibition of pathogenic bacterial overgrowth is often associated with terminating free radical formation (Ak & Gülçin, 2008). It is beyond the scope of this article to outline how every type of inflammatory mediator and free radical is associated with different diseases and how curcumin influences clinical outcomes behind these illnesses but this overview should outline curcumin’s therapeutic value in managing chronic inflammation.

Anti-cancer effects

Curcumin’s anticancer effects are broad, and include suppressing cancer cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis (cell death), inhibiting angiogenesis (formation of blood supply in tumours), and supressing the expression of proteins that inhibit apoptosis whilst protecting the immune system of the afflicted. The crux of cancer development is thought to be rooted in aberrant cell cycle progression and curcumin can assert anti-tumour activity by altering de-regulated cell cycles, via cyclin (regulatory proteins that drive DNA synthesis and cell division)-dependent, and p53 (genes that induce cell-cycle arrest and cell death)-dependent and independent pathways. From a prevention standpoint, curcumin has been associated with regression of pre-malignant lesions of the bladder, soft palate, GI tract, cervix, and skin, and doses up to 10 grams per day could be taken by patients with pre-malignant lesions for 3 months without signs of toxicity (Sa & Das, 2008).

Curcumin asserts part of its anti-cancer effects by interfering with signalling molecules that trigger genes that drive pro-cancer metrics, such as inflammation, suppressing apoptosis, mediating proliferation, cell invasion, and angiogenesis. NF-kB and STAT3 are good examples of signalling molecules that have been implicated in many cancers, including breast, prostate, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, multiple myeloma, lymphomas and leukemia, brain, colon, gastric, esophageal, ovarian, nasopharyngeal and pancreatic cancer, and curcumin has been shown to inhibit both STAT3 and NF-kB signalling pathways. Curcumin can also directly inhibit cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest and stimulate apoptosis by modulating signalling molecules that promote these processes (Vallianou et al, 2015). For example, it has been noted in colorectal cancer research that curcumin inhibits NF-kB action on the mucosa of the colon and initiates apoptosis of colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. Additionally, turmeric could be a useful adjunct to allopathic cancer treatments, as turmeric has been shown to increase the sensitivity of tumour cells to chemo-drugs, such as capecitabine and taxol, and can also increase the sensitivity of lymphoma cells to ionising radiation-initiated apoptosis (Ahmad et al, 2020).

Metabolic/cardiac effects

Metabolic syndrome is a multifactorial condition involving derangements in blood glucose, blood pressure, triglycerides and body composition, and is considered to be a major risk factor for chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes. Curcumin can reduce LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels in cardiovascular disease patients and can reduce lipid peroxidation in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia, which reduces cardiovascular risk factors. A meta-analysis involving seven randomized controlled trials revealed that curcumin can significantly improve fasting blood glucose, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol (good cholesterol), and diastolic blood pressure. Decreasing tumour necrosis factor-a, plasma free fatty acids, oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and NF-kB, appear to be the underlying mechanisms through which curcumin asserts its anti-diabetic effects and cardiovascular benefits (Azhdari et al, 2019).

Furthermore, curcumin plays a role in decreasing adipogenesis by suppressing proteins that signal the genes that drive it and by lowering cholesterol levels. Improving insulin sensitivity is a hallmark goal in reducing metabolic syndrome risk and curcumin can up-regulate the gene expression of pancreatic glucose transporter 2, 3, and 4 (GLUT 2, 3, and 4), thus stimulating insulin secretion. The above-mentioned antioxidant benefits of curcumin could prove valuable in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, a condition where fat accumulation in the liver equates to greater than 5% of the liver’s weight and over 70 % of those with type 2 diabetes suffer from, as NAFLD involves oxidative stress processes and damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA. Liver enzymes, such as alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) have shown to be significantly decreased following curcumin supplementation, indicating that curcumin has protective effects on the liver (Jabczyk et al, 2021).

Anti-microbial effects

The antimicrobial properties of turmeric are not attributed to curcumin because turmeric contains a broad range of compounds, such as phenolic compounds, curcuminoids, curcumins, turmerol and veleric acid, which have shown to be active against bacillus subtilus, bacillus coagulans, bacillus cereus, staphylococcus aureus, pseudomonas aeruginosa and escherichia coli. These phenolic compounds interact with membrane proteins, causing cell membrane disturbance, disruption of cell wall and electron transport chain damage, rendering the microbe incapable of producing energy. Additionally, curcumin has shown significant activity against parasite forms of the protozoa Leishmania amazonensis, which causes the infection leishmaniasis. Oil preparations of turmeric have also proven to be effective against a variety of different fungi, inhibiting growth of aspergillus parasiticus, fusarium moniliforme, penicillium digitatum and aspergillus flavus by up to 70% (Nisar et al, 2015). Given that humans harbour both beneficial and potentially pathogenic microbes, it would be reasonable to ensure that any antimicrobial compound/substance that we ingest does not have a range of antimicrobial effects that is so broad that it also inhibits the growth of beneficial flora. In a study using methanol extract of turmeric against different bacterial strains, strong inhibitory activity was noted against clostridium perfringens but no inhibitory effect against beneficial strains, such as bifidobacterium adolescentis, bifidobacterium bifidum, bifidobacterium longum and lactobacillus casei (Lee, 2006).

Neuro-protective effects

Curcumin has proven to have significant neurological benefits via a variety of mechanisms, some of which I have already mentioned. Considering cerebral ischemia/stroke as an example, insufficient blood and nutrient supply to the brain leads to energy failure, ATP depletion, and glutamate (an excitatory neurotransmitter) excitotoxicity in neurons, which increases calcium overload, the release of pro-inflammatory mediators, and disruption in blood-brain barrier integrity. Curcumin can protect neurons from oxidative stress by neutralizing free radicals, reactive oxygen/nitrogen species and enzymes that drive inflammation, whilst increasing neuroprotective factors, such as succinate dehydrogenase (an enzyme involved in energy production), HDL cholesterol, superoxide dismutase, glutathione and catalase, which are 3 crucial proteins/enzymes for protecting neurons from lipid peroxidation (Subedi & Gaire, 2021).

These mechanisms are also precisely why turmeric could be a useful therapeutic aid in managing the symptoms and improving clinical outcomes in neurodegenerative disorders, as Parkinson’s disease, for example, involves neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, DNA damage, lipid peroxidation, glutathione depletion, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Additionally, research done on live animals suggest that curcumin can prevent protein aggregation and induce neurogenesis, either of which are paramount for treating neurodegenerative conditions. In a model of traumatic brain injury, rats given curcumin were protected against synaptic dysfunction and cognitive deficits, which can be partly attributed to curcumin’s ability to increase the neuron protector and growth stimulator, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Mythri & Bharath, 2012).

References

Ahmad, R.S., Hussain, M.B., Sultan, M.T., Arshad, M.S., et al. (2020). Biochemistry, safety, pharmacological activities, and applications of turmeric: a mechanistic review. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine, 2020.https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7656919

Ak, T., & Gülçin, I. (2008). Antioxidant and radical scavenging properties of curcumin. Chemico-biological interactions, 174(1), 27-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2008.05.003

Azhdari, M., Karandish, M., & Mansoori, A. (2019). Metabolic effects of curcumin supplementation in patients with metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Phytotherapy research, 33(5), 1289-1301. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6323

Boroumand, N., Samarghandian, S., & Hashemy S.I. (2018). Immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects of curcumin. Journal of herbmed pharmacology, 7(4), 211-219. https://doi.org/10.15171/jhp.2018.33

Jabczyk, M., Nowak, J., Hudzik, B., & Zubelewicz-Szkodzińska, B. (2021). Curcumin in metabolic health and disease. Nutrients, 13(12), 4440. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124440

Kaur, A. (2019). Historical background of usage of turmeric: a review. Journal of pharmacognosy and phytochemistry, 8(1), 2769-2771. https://www.phytojournal.com/archives/2019/vol8issue1/PartAT/8-2-135-332.pdf

Lee, H. (2006). Antimicrobial properties of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) rhizome-derived ar-turmerone and curcumin. Food science and biotechnology, 15(4), 559-563. https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO200609905845183.pdf

Mythri, R.B., & Bharath, M.M.S. (2012). Curcumin: a potential neuroprotective agent in parkinson’s disease. Current pharmaceutical design, 18(1), 91-99. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161212798918995

Nisar, T., Iqbal, M., Raza, A., Safdar, M., et al. (2015). Turmeric: a promising spice for phytochemical and antimicrobial activities. American-Eurasian journal of agricultural and environmental science, 15(7), 1278-1288.https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tanzeela-Nisar/publication/307544435_Turmeric_A_Promising_Spice_for_Phytochemical_and_Antimicrobial_Activities/links/57c7caf508ae9d64047ea6b2/Turmeric-A-Promising-Spice-for-Phytochemical-and-Antimicrobial-Activities.pdf

Sa, G., & Das, T. (2008). Anti cancer effects of curcumin: cycle of life and death. Cell division, 3, 14.https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-1028-3-14

Subedi, L., & Gaire, B.P. (2021). Neuroprotective effects of curcumin in cerebral ischemia: cellular and molecular mechanisms. ASC chemical neuroscience, 12(14), 2562-2572. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.1c00153

Vallianou, N.G., Evangelopoulos, A., Schizas, N., & Kazazis, C. (2015). Potential anticancer properties and mechanisms of action of curcumin. Anticancer research, 35(2), 645-651. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Natalia-Vallianou/publication/272148517_Potential_Anticancer_Properties_and_Mechanisms_of_Action_of_Curcumin/links/54eef4bd0cf2e55866f3bd51/Potential-Anticancer-Properties-and-Mechanisms-of-Action-of-Curcumin.pdf

Leave a comment